Part 1: The game

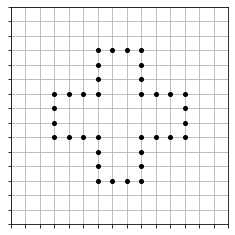

When I was a teenager, I used to play a pen-and-paper game called morpion solitaire (sometimes also join five, or simply the line game). The goal of the game is to draw as many lines and dots on a piece of paper following some simple rules. To begin with, take a piece of graph paper and draw 36 dots in a cross pattern:

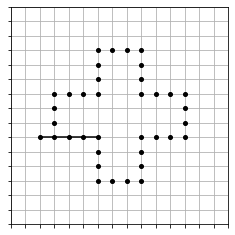

The rules say that you are allowed to add a point if you can draw a line that goes through that point and four other points that are there already. This is an example of a first move:

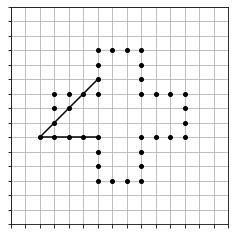

The lines can be horizontal, vertical, or diagonal, but always four squares in length. The new point need not be at an extremity of the line, it can be anywhere along it. For instance, after the first move made above, it is possible to draw the diagonal line:

The lines can cross, but they are not allowed to overlap. This means that the grid is slowly going to fill up, and at some point it might happen that no more moves are possible. At this stage the game is over, and your score is given by the number of points you drew on the grid (not counting the initial 36 points). Here is an animation showing a complete game:

The final score says 34. This is a pretty low score: if you try by yourself, I bet you will easily do better than that!

Playable versions of the game can be found as cell phone apps, or on the internet, for instance at joinfive.com.

The world record

The current world record was established in 2011 at 178 points. This feat was achieved by a professional using an advanced Monte-Carlo algorithm.

Can this record still be beaten? In principle yes! There is no proof that this grid is the optimal one. However, it is clear that this won’t be easy. In fact, it has been proven that this is a NP-hard problem (lots of interesting considerations are made about the game at the great website www.morpionsolitaire.com).

But maybe the most incredible fact is that until 2010, the world record was an impressive 170 obtained by a human back in 1976! It looks like computers are not so much better than humans at this simple little game.

Let the computer play (in a dumb way!)

This got me wondering whether I can approach (or improve!) the world record with deep learning. But before talking about neural networks, it is worth taking a look at the simplest algorithm. I wrote a Python module to emulate the game (more on this in Part 2), and now I can let the computer play at random by picking at each step one move among all possible moves. I let the computer play 100,000 games in this way, and the best score it obtained was… 86!

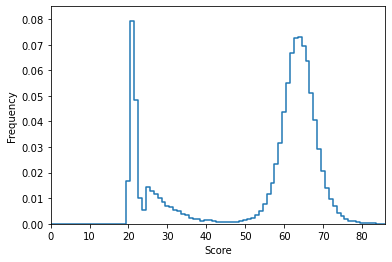

This is far from the world record. Very far, actually! And most games ended with scores lower than that. Here is a distribution of all the end scores obtained by the computer:

Despite simple rules, the dynamics of the game is very interesting: many random explorations end with a miserable score of about 20-25 points (the absolute minimum is 20 points), but once the 45-points bottleneck is passed, they are again many more possible outcomes, with a peak around 65 points.

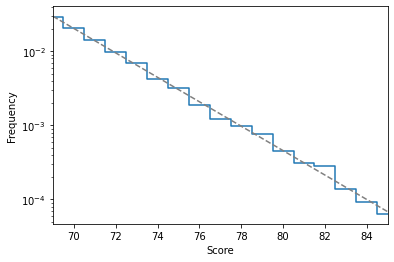

If we zoom on the scores above 70, we see that the frequency decays exponentially:

This gives us an estimate of what would be needed to reach a score of 100 by purely random exploration: around 5 million games. This could certainly be done, but it is a very inefficient strategy. And there is no hope to approach the world record in this way!

In conclusion, trying to reach high scores from a purely random exploration is a very dumb idea.

Humans know better

I already told you to try playing by yourself. Did you do it? If you did, I bet that you got in the ballpark of what my dumb computer implementation reached. With a bit of practice one can do much better than that. For instance, here is an animation of my latest pen-and-(electronic-)paper attempt:

I got to a score of 124. Not bad, huh? For sure I had a little practice, but I didn’t need hundreds of thousands of games to get there. It looks like I’m nearly as close to the world record as I am to the best random game.

How did I get there? There are basically two strategies that make me play better than picking a move at random:

- I can imagine the game a few moves ahead. Not dozens of moves, but at least just a few. In this way I can easily gauge whether a given move will open up more possibilities ahead, or whether it won’t.

- After playing a few games I developed a feeling for what kind of features are good and what kind are bad. For instance it is not only pleasing for the eye but also efficient if the grids is filling up some region as much as possible, meaning that all points and lines (horizontal, vertical and diagonal) are drawn there. Empty segments between lines are useless, and I try to avoid them as much as possible.

These strategies are not easy to implement in an algorithm. The first one requires exploring tons of possibilities, whereas the second one is just impossible to formulate. And of course my strategy might not be the winning one.

However, I’m sure that you are now seeing why this is a good problem for deep learning!

Deep learning Morpion Solitaire

Evaluating the potential of a given move is something that a deep neural network should be able to do. Like in computer chess, one can evaluate the situation at any given step of the game, for instance asking for an estimate of the number of moves that one can expect to make. This estimate can be very precise when there are only a few moves left, or quite rough at the beginning of a game. In any case, the reach of a computer exploration can be vastly improved if the next move is decided based on this approximate evaluation: if I can combine the ability of the neural net to assess the situation in the same way as I do when I play, together with the possibility to play many many games (which I don’t have), then I hope to reach interesting results.

In this series of blog posts, I’m going to describe my attempts to implement a deep learning algorithm for Morpion Solitaire. I should warn you that I am by no means a professional. I’m rather using this interesting problem as a way to learn about artificial intelligence. Therefore, I will take it step-by-step, beginning in Part 2 with some general considerations about the implementation, then in Part 3 with a simple version of the problem.

I’m not sure yet how far this will bring us. But I’m truly enjoying learning about a this exciting topic, and I’m happy to take you along on this journey. Let’s see how far we can get together!